The Nature of Reality: Is Consciousness All There Is? (Part 1)

Do we see the world as it really is? I describe and discuss Hoffman's evolutionary game theory approach to answering this question.

Mark Baumann

November 8, 2021

Neuroscientist and human vision expert Donald Hoffman published a book in 2019 entitled The Case Against Reality: Why Evolution Hid the Truth from Our Eyes [1]The Case Against Reality: Why Evolution Hid the Truth from Our Eyes by Donald Hoffman based on his research into vision and consciousness — in particular, a 2014 paper he published in Frontiers of Psychology [2]Hoffman Donald D., Prakash Chetan, “Objects of consciousness”, Frontiers in Psychology vol 5, 2014 with co-author Chetan Prakash, a mathematician. Since publishing his book, Hoffman made the rounds on several podcasts[3]TED Interview (runtime 55 mins)[4]Science Salon interview with Michael Shermer (runtime 1h 45m), which is how I learned of his work.

Hoffman and his colleagues have proposed a new philosophy on the nature of reality that they call “conscious realism”. In their philosophy, reality is consciousness. The physical world doesn’t exist. Only consciousness(es) exist.

How did Hoffman come to such an intriguing conclusion? In an interview with Michael Shermer[5]Science Salon interview with Michael Shermer (runtime 1h 45m), Hoffman stated that he’s been contemplating his ideas about conscious realism for 20 years, though more seriously for the last 10 years.

In this two-part series, I’ll summarize his arguments and conclusion, and offer my thoughts along the way.

A Snake in the Grass: Does Fitness Equal Reality?

To understand how Hoffman arrived at his conclusions it helps to begin with his background and research. Hoffman studied computer vision at MIT’s Artificial Intelligence lab and is now a professor of neuroscience at U.C. Irvine. His research revolves around evolutionary game theory, in which he applies the mathematical theory of games to draw conclusions about evolutionary processes.

In the course of his research, Hoffman has arrived at the conclusion that natural selection does not favor truth. Let’s unpack this idea.

Selection does not favor truth

Natural selection, by definition, is the process by which organisms that are better adapted to their environment will survive and reproduce. Fitness is defined to be the likelihood that an organism will survive and go on to have offspring (and how many). The higher the fitness, the more successful the organism is at producing future generations that share its genetic information.

Hoffman is claiming that seeing “truth” (i.e., seeing the world as it really is) is not a necessary ingredient for having high fitness. I think this is more easily illustrated with an analogy, so I’ll use Hoffman’s snake-in-the-grass analogy.

Garden hose or snake?

(Image credit: Reddit user rocketman1706)

Snake or garden hose?

Imagine a young man is walking through tall grass and spots a long, winding object in the grass ahead. Is it a venomous snake? Or is it just a garden hose?

Suppose it actually is a venomous snake. If he reacts as if it’s a venomous snake and gives it a wide berth, then he’s spared himself from being bitten and killed, which means a higher fitness score since now he’s more likely to go on and have children. If he reacts as if it’s a garden hose and traipses ahead without concern until he is bitten and killed, then his error has cost him his life before he could have offspring, giving him a fitness score of zero.

Now, suppose it’s actually a garden hose instead of a snake. If the youth reacts as if the garden hose is a venomous snake and avoids it, he’s lost little other than a waste of energy (though this wasted energy could be important — we’ll discuss energy more in a minute). If the youth walks on ahead with the assumption that it’s a garden hose, nothing is lost or gained.

Reacting to a long winding object in the grass as if it were a venomous snake has a higher fitness value than reacting to it as if it were a garden hose. That’s because avoiding it, even if it’s just a garden hose, improves the likelihood that one will go on to have offspring.

As far as perception is concerned, fitness depends less on whether the perception is accurate (seeing it for what it really is, a garden hose or a snake) and more on whether perception leads to behavior that improves the chances of living long enough to have children. If the youth always reacts to the winding object in the grass as if it were a venomous snake, even when it’s just a garden hose, this improves his fitness score despite the lack of accuracy in perceiving it as a snake or a hose.

In their paper, Hoffman and Prakash summarize it as: “Perception is not about truth, it’s about having kids.” [6]Hoffman Donald D., Prakash Chetan, “Objects of consciousness”, Frontiers in Psychology vol 5, 2014

How could non-truth be better than truth?

For the purposes of fitness, wouldn’t accurately perceiving the world as it really is work just as well as any non-accurate perception of the world? For example, if one accurately perceives the snake to be a snake, then the resulting avoidance behavior will ensure they avoid being bitten. And if one accurately perceives the hose to be a hose, then the resulting lack of avoidance behavior will not be harmful. That is, an accurate perception of the world has a high fitness value. If one accurately perceives reality, this must be at least as good as any inaccurate perception of reality, doesn’t it?

Hoffman would likely respond to my objection with this statement from his paper: “…natural selection does not favor perceptual systems that see the truth in whole or in part. Instead, it favors perceptions that are fast, cheap, and tailored to guide behaviors needed to survive and reproduce.” [7]Hoffman Donald D., Prakash Chetan, “Objects of consciousness”, Frontiers in Psychology vol 5, 2014

Hoffman’s argument is that while perceiving reality accurately is good for your evolutionary fitness, such accurate perceptions might be costly in terms of energy or time. In the competitive landscape of natural selection, fast and cheap (but inaccurate) perceptions might outpace more energy-expensive (but accurate) perceptions.

As he summarizes it in an interview with Quanta Magazine: “Evolution shapes acceptable solutions, not optimal ones.” [8]The Evolutionary Argument Against Reality, Quanta Magazine, April 21, 2016

Evolutionary Games

So far, Hoffman has argued that evolutionary biology doesn’t rule out the possibility that our perceptions could be inaccurate. His next step is to suggest, based on results from his computer simulations, that optimal perceptions are “driven to extinction” in favor of cheap but acceptable perceptions. Now let’s unpack that idea.

In the paper “Natural selection and veridical perceptions” by Justin Mark, Brian Marion, and Donald Hoffman (hereafter “MMH”) [9]Mark, Marion, and Hoffman, Natural selection and veridical perceptions, Journal of Theoretical Biology 266 (2010) 504–515 (pdf), published in the Journal of Theoretical Biology in 2010, the authors describe an “evolutionary game” that led them to draw their conclusion that cheap inaccurate perceptions will win out over expensive accurate perceptions.

The two-player game

Imagine a two-player game in which two agents are competing for territory based on the resources contained in the territories. There are two resources, food and water. And there are two strategies for selecting a territory: a simple strategy and a truth strategy.

The simple strategy looks at just one resource, for example food, and selects the territory that has the most of that type of resource. If it’s a tie, it chooses one at random. Both resources (food and water) are necessary for survival, but the simple strategy makes a decision based on only one of the two resources (food, in this case).

The truth strategy looks at both resources — food and water — and chooses the best overall territory based on both quantities present.

Because “seeing more data takes more time”, the simple strategy gets to choose and claim its territory first. The truth strategy will then select its territory second, after the simple strategy has already claimed one.

Also, both strategies must pay the energy price for collecting information by subtracting the energy cost from whatever it earns. Since “seeing more data takes more energy”, and since the truth strategy collects more information, the truth strategy will be paying a higher “energy tax” on its “earnings”.

Can a quick, low-cost strategy that has imperfect information (the simple strategy) succeed against a strategy that has perfect information (the truth strategy)?

Monte Carlo simulations

MMH run many simulations of this game in virtual environments populated with randomly-distributed food and water resources. Because of the random nature of each run of the simulation — not unlike rolling dice over and over — such an approach is often called a Monte Carlo approach in computational science circles, named for the famous casino in Monaco.

Aggregating the results of their numerous Monte Carlo simulations, MMH find that the simple strategy can and does win against the truth strategy in many cases. They state: “We find that the costs in time and energy charged to truth can exceed the benefits it receives from perfect knowledge, so that truth ends up less fit than simple.” [10]Mark, Marion, and Hoffman, Natural selection and veridical perceptions, Journal of Theoretical Biology 266 (2010) 504–515 (pdf)

Analysis of the simulation results

Some questions I have at this point are: Just how costly should it be to use more energy? Granting the assumption that it takes more energy to see more data, how much extra energy does that cost? What happens if we relax the energy cost penalty altogether?

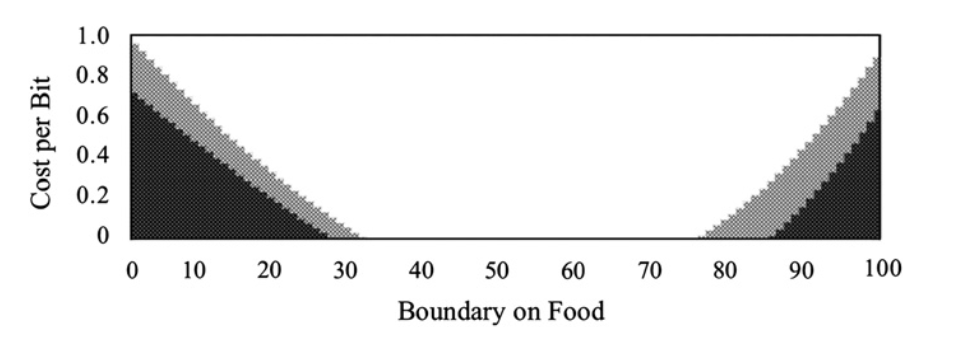

To help answer questions like these, MMH have made the energy cost into a tunable parameter in the evolutionary game. They call it the “cost per bit” since it denotes the energy cost per bit of information gathered. You can think of it as an “information tax” on the information (bits of data) acquired. They ran their simulations with different values for the “cost per bit” and the results are summarized in the graph below.

Energy cost per bit of information vs “pickiness” of simple strategy (Image credit: Hoffman and Prakash[11]Hoffman Donald D., Prakash Chetan, “Objects of consciousness”, Frontiers in Psychology vol 5, 2014)

The vertical axis in the graph is the energy cost per bit of information gathered by the agent.

The horizontal axis shows what I’m calling the “pickiness” factor of the the simple strategy, where 0 means it is not picky at all about which territory it chooses (effectively picking a territory at random every time) while 100 means it only picks a territory if it has the maximum possible amount of food, and randomly otherwise. This means that for both high and low pickiness, the simple strategy will be doing a lot of picking at random.

There are relatively few white points in the leftmost and rightmost regions of the graph. This indicates that if the simple strategy is either “too picky” or “too lax” (and it therefore ends up choosing at random most of the time, as discussed) then it doesn’t do well.

There are relatively few black points in the upper regions of the graph. Therefore, as the energy cost for information goes up, the truth strategy does worse. This is expected since the truth strategy is spending more energy to acquire more information than the simple strategy, and the more costly that information becomes the worse it will be for the truth strategy.

Perhaps surprisingly, even when the cost for information is zero (the bottom-most boundary of the graph), the simple strategy (white) still wins about half of the time.

For MMH, the salient feature of the above graph is this: the simple strategy (white) can and often does win against the truth strategy (black), sometimes driving the truth strategy to extinction. This is how they support their conclusion that evolution does not favor truth.

As MMH themselves note, however, the simple strategy doesn’t always drive truth to extinction. “Our simulations do not find that natural selection always drives truth to extinction. They show instead that natural selection can drive truth to extinction.” [12]Mark, Marion, and Hoffman, Natural selection and veridical perceptions, Journal of Theoretical Biology 266 (2010) 504–515 (pdf)

So they’re saying it’s possible that truth can be driven to extinction, but not certain. This is a major caveat in their case that evolution “drives truth to extinction”. To say that something is possible is obviously different than saying that something is certain. They’re drawing a much stronger conclusion than their computational evidence would imply.

In the conclusion of their paper, MMH highlight several areas where the computer simulations can be improved, including (1) making the resources time-variant so that they more realistically represent nature, which is always changing; (2) considering additional foraging strategies besides simple and truth; (3) giving agents the ability to learn, rather than use the same foraging strategy for their entire lifespan; and more.

Based on these simulations, despite their shortcomings, the strong conclusion they’ve drawn is this: we do not see reality as it really appears, because to do so would violate the natural course of evolution.

Reality Is Not As It Appears

OK, suppose our perceptions of reality are inaccurate. But are they still useful?

Hoffman offers another analogy, that of the desktop icon. The desktop on our computer screen is a useful interface for interacting with the contents of our computer. An icon on the desktop might represent a file on the computer’s hard drive. To assume that the icon is literally the file, however, is erroneous. If the icon is blue and rectangular, that doesn’t mean the file itself is blue and rectangular.

Analogously, the reality that we perceive is like a computer desktop with its icons. A deeper reality exists beneath the desktop, analogous to the inner workings of the computer.

And although the icon might not literally be the file, it is still important. Dragging the icon to the trash will delete our file, which might be a crucial error if that file contains the working draft of our Ph.D. thesis, for instance. As Hoffman says, “It’s a logical flaw to think that if we have to take it seriously, we also have to take it literally.” [13]The Evolutionary Argument Against Reality, Quanta Magazine, April 21, 2016 Similarly, the snake in the grass should be taken seriously and avoided, even if it is only an icon on our desktop.

I agree that our senses may not be trustworthy. This was the fundamental premise in the Meditations on First Philosophy by Descartes, published in 1641. Descartes begins by assuming that all of his senses are deceiving him, and that he cannot trust any of his perceptions of reality. He goes a step further and supposes that even self-evident truths might be a deception. He then asks: what can I know for sure despite that my senses and even my thoughts could be deceiving me? His answer: he knows that he has thoughts. And since he has thoughts, he therefore knows that he is a “thinking thing”. Hence his famous statement: cogito ergo sum, “I think therefore I am”. (From there, Descartes proceeds to prove that he can also know that God must exist. If this all sounds interesting to you, I recommend reading his Meditations on First Philosophy!)

So I do not believe Hoffman has tread any new philosophical ground here that wasn’t already tread by Renes Descartes, and later George Berkeley, in earlier centuries. That our senses may be deceiving us is a well-studied premise in philosophy.

What Hoffman offers, perhaps, is an argument that evolutionary biology at least does not rule out the possibility that our senses are deceiving us and, if his Monte Carlo simulation results are valid, it is likely that our senses are deceiving us about the true nature of reality since that is (according to Hoffman) the inevitable outcome of the evolutionary process.

Coming Up in the Next Article

Now that we’ve unpacked Hoffman’s arguments for why reality is not what we perceive it to be, in part two I’ll show how he builds on this and ultimately argues that consciousness is all that exists.

Read Part Two Now!

Footnotes